Decreasing disparities in newborn screening across the United States

EveryLife Foundation advocates on behalf of the rare disease community for legislation and policy that advances the development of and access to lifesaving diagnoses, treatments, and cures.

I spoke with Annie Kennedy, Chief of Policy, Advocacy, and Patient Engagement, about the organization's efforts to enhance the existing US newborn screening program.

Interview with Annie Kennedy

What is the current state of newborn screening in the United States?

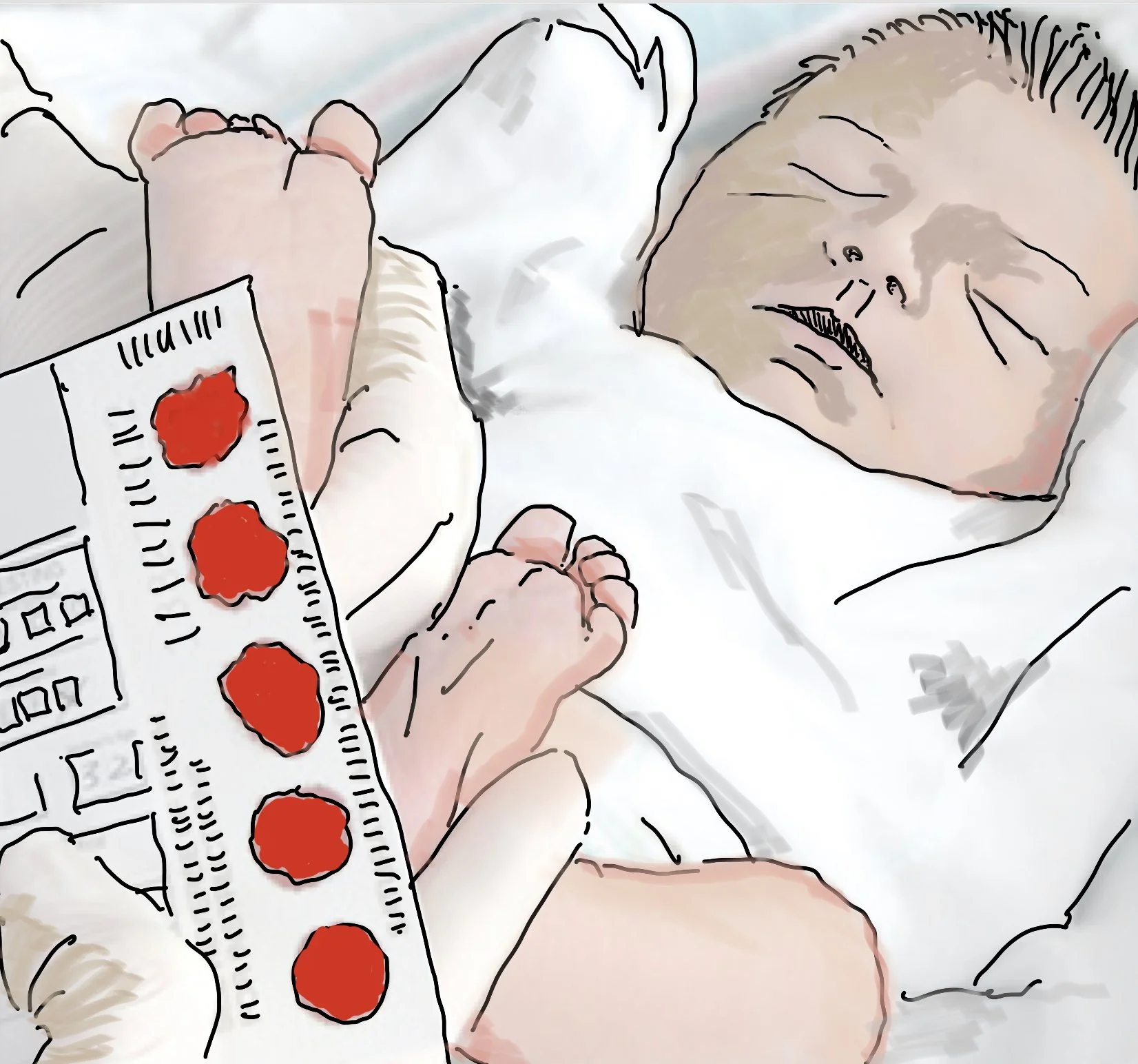

In the US, newborn screening (NBS) is seen as one of the nation's most successful public health programs, with about 4 million newborns screened each year, of which 1 in 300 has a condition that can be detected through NBS.[1] Typically, screening is done through a dried blood spot taken from pricking the heel of a newborn, and tests are conducted on the dried blood spot.

At the national level, the Secretary of Health and Human Services provides the authority to the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders and Genetic Diseases in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) to advise on a federally recommended newborn screening panel. The ACHDNC developed a rigorous evidence review process to evaluate conditions before placement in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). Considerations include:

The condition can be reliably detected with screening technology

The condition can be treated or otherwise benefit from early intervention

There is an adequate follow-up infrastructure in place

Patient advocacy groups usually nominate a condition for the panel and present evidence of pilot studies that prove the effectiveness of a screening program for this condition in the US.

Once a condition is added to the RUSP, states conduct evaluations through State Advisory Committees or legislative processes to determine whether to add the condition to their screening program. The process is not automatic. Each state has different criteria, including the cost of adding the condition to their newborn screening program, whether state laboratories have the technology available to screen for the condition, whether the proper infrastructure exists within the birthing centers, etc.

This process results in a lot of disparity in screening practices between states; some states screen for as few as 31 conditions, and others screen for as many as 60, depending on each state's capacity, resources, and priorities. In addition, beyond the 36 conditions recommended in the RUSP, some states screen for additional conditions, which have not yet met the requirements of the federal recommended panel, but have been added through the state's legislative processes. So, in the United States, the conditions for which a child is screened at birth – and all these conditions are potentially life-altering or life-threatening, many of which have life-changing interventions available at the time of birth – are 100% determined by the state in which the child is born.

From our perspective in the rare disease community, it is not acceptable that a child receives life-altering interventions or not based on the state the child was born. This is not something that families or healthcare providers should have to endure.

So, what is EveryLife working on to decrease disparities in screening?

At EveryLife, we work on policy that removes obstacles to lifesaving interventions and share knowledge that empowers families to understand the condition their child was born with and the intervention(s) that may improve their child's health outcomes.

At the state level, we are working on legislation that would reduce the time between when a condition is added to the federal RUSP and when it is added to the state's screening panel. In some cases, it can take up to a decade for a condition to be added to all 50 state panels. We do not think it is acceptable that after the Secretary of Health and Human Services and an advisory committee of experts have recommended screening for a condition, barriers such as resources and infrastructure prevent states from adding the condition in a timely manner. For this reason, we have been working with states to implement RUSP alignment legislation. With the states, we identify the requirements and resources needed to ensure the timely adoption of new conditions added to the federal RUSP and establish reasonable timelines for implementation within the state, usually two to three years.

We started this work in 2016 in California and, to date, have passed RUSP alignment legislation in 10 states (AZ, CA, FL, GA, IA, MD, MS, NC, OH, PA), with two additional states expected in 2023 (TX, WI). So, by 2023, more than 50% of children in the US will be born in states with RUSP alignment legislation, which is a huge milestone for us.

At a federal level, our community is concerned that the newborn screening system is not sustainable how it was initially established, particularly given the number of new therapies developed yearly. The impact on those keeping the system going is tremendous right now; for example, those working in the state health labs and the birthing centers are stretched at this moment. We are currently partnering with March of Dimes and other national health organizations to work on opportunities to sustain existing funding of this public health system and enhance and modernize the system to serve our nation's newborns better.

The Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act (P.L. 110-204), passed in 2008, and reauthorized in 2014 (P.L. 113-240), expired on September 30, 2019.[1] We are advocating to reauthorize the legislation through the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Reauthorization Act of 2021 (H.R. 482 / S. 350), which is currently under debate in the Senate over consent issues. In parallel, we are reviewing the legislation to understand the critical elements needed to keep this public health infrastructure going, as well as opportunities to modernize and enhance the screening program, and identifying alternative ways to get this language passed into legislation. One key success was the inclusion of language funding a National Academy of Medicine study to review the current NBS landscape and make recommendations for enhancements in the FY23 Omnibus. We are also working on appropriations to ensure sufficient funding for public health agencies, such as the National Institute of Health.

During the summer of 2022, we organized NBS modernization roundtables, including town hall meetings and smaller meetings around the country with NBS experts. We are using the action items and ideas discussed as a policy roadmap for modernizing the system.

What are you looking forward to accomplishing in 2023?

I am encouraged and excited about 2023. Part of the reason we have bottlenecks in the system is that so many new therapies are being developed, and this means many new opportunities to serve babies born with previously untreatable conditions. If we can screen and detect children for these conditions, we can now do something for them, and that is an amazing opportunity. The advent of new therapies is building a sense of urgency and unprecedented collaboration in the community across coalitions, federal agency partners, clinical experts, and the pharmaceutical industry – and this is all powered by patient community experts invested in NBS. Ten years ago, when I worked on the previous Reauthorization Act, this level of collaboration between the patient community and federal and state partners did not exist. Now everyone is sitting together, thinking about how best to serve all stakeholders in this environment and ecosystem. I am also enthusiastic about the new Congress and the opportunity to identify new congressional champions to help build on the successes of 2022. Particularly for the newborn screening Reauthorization Act, we have a chance to go back to the drafting board and propose something new that will better serve our nation's newborns. We can only win when we work together as a community.

Reference:

[1] https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/MOD_NSSLRA_MOD_Logo_111422_vfinal.pdf

About the Interviewee

Annie Kennedy is chief of policy, advocacy, and patient engagement, at EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases. Focused on improving health outcomes for people living with rare diseases by advancing the development of treatment and diagnostic opportunities for rare disease patients through science-driven public policy, Annie’s work includes building strong partnerships with policy makers, federal agencies, industry, and alliances.

Annie has served within the community for nearly three decades through her roles with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA). In that time, she helped lead legislative efforts around passage and implementation of the MD-CARE Act (2001, 2008, 2014) and the Patient Focused Impact Assessment Act (PFIA), which became the Patient Experience Data provision within the 21st Century Cures Act (section 3001). She has engaged with the Food and Drug Administration and industry around regulatory policy and therapeutic pipelines, led access efforts as the first therapies were approved in Duchenne, and engaged with the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review around the development of the modified framework for the valuation of ultra-rare diseases.